A complaint made by Samasera Bahādura Pā̃ḍe re the Rājakumārī Pãḍenī case case (VS 1934)

ID: K_0175_0018

Edited and

translated by Rajan Khatiwoda

in collaboration with

Simon Cubelic

Created: 2015-04-29;

Last modified: 2018-06-19

For the metadata of the document, click here

The accompanying edition, translation/synopsis and/or commentary are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Abstract

This document is a complaint (ujura) made by Samasera Bāhādura Pā̃ḍe, an inhabitant of Naradevī Ṭola in Kathmandu, against his kākī (wife of his father’s brother) Rājakumārī Pãḍenī. She is accused of meeting her by then incestuous husband, Pṛthī Bahādura Pā̃ḍe, accepting rice from him and having sexual intercourse with him.Diplomatic edition

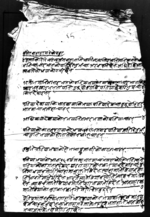

[1r]

⟪६६⟫1संसेरवाहादुरपाडेकोउजुर2४पुस्ताकिदिदिभाउज्यूसंगवातलागिभागीजान्यासितजानिजानिसगगै[?]

3भतिन्यालाइभातकोपति⟪या⟫दीनुभंन्याअइनपनिछैनअघिदेषिआ[...]

4म्मकसैकोभयाकोपनीछैन¯¯¯¯१

5१८सालमानिजलाइभातकोपतियाभयाकोभयाभताहालाइभातकिन

6ष्वाइनन् ष्वाइनन्तापनिगुरुप्रोतराषिपतियादेषाउनुपर्न्याहो

7किनदेषाइनन्¯¯¯२

8पतियादेषायाकिभातष्वायाकिभयापतियादेषन्यागुरुप्रोहितर

9भातषान्याभताहाल्याउन्¯¯¯३

10अघिष्वायादेषायाकोनभयानिजलाइभयाकोपतियाल्याउन्¯¯¯४

11पतियाकोकागजहरायाकोभयाअदालतवाटपतियागरिदिनुभं

12न्यापुर्जिभयाकोहोलातेस्कोनकल्ल्याउन्¯¯¯¯५

13हुकुंलेपतियाभयाकोहोभन्याप्रमान्गीकोकागजल्याउन्¯¯¯६

14पतियाभयाकोआज१६वर्षसम्मभातषान्याभताहाकोहिननिस्कने

15पतियाकोकागज्नदेषाइयउटाफारकोनकल्मात्रदेषाउन्यापु

16र्जिमाभयावमोजींस्याहामाकुरालेषिदैनस्याहामालेषियावमो

17जिंआवर्जेमालेषीदैनआवर्जेमालेषियावमोजिंज्माषर्चमालेषि

18दैनज्माषर्चमालेषियावमोजिंफारकमालेषीदैनआजफारक

19मालेषियाकोकुराकानक्कल्लेमेरोचित्तवुझ्दैन¯¯¯७

20येतिप्रमाणनवुझिभताहालेभातषायाकोनभयापनिअवषानुप

21र्छभंन्याहुकुंहुंछभन्याभताहासवैसामेलहउन्भताहालेभातषांछु

22भन्यामसामेलछुमेरोउजुरछैन¯¯८

Translation

[1r]

661

A complaint [made] by Samasera Bahādura Pā̃ḍe.

There is no Ain2 that grants rice expiation (patiyā) to such a person who accompanies and willingly eats rice with [someone] who has fled after commiting adultery with the [non-widowed] (sadhavā) wife of a 4th-generation cousin and with a 4th-generation female cousin. [Such expiation] has never been granted to anyone up till today. --- 13

If the rice expiation was granted to her in [Vikrama era year 19]18 (1861/62 CE), why has she not fed rice to someone of the same caste (bhatāhā) [since then]?4 She has not fed [any such person], but still she should have borne witness to the expiation by inviting a Brahmin priest (gurupurohita) [to accept rice from her]. Why has she not borne witness to [it]? --- 2

If she has borne witness to the expiation [or] fed rice to someone of the same caste, let her bring forward [as corroborators] the witnessing Brahmin priest and fellow caste member who ate [her] rice. --- 3

If there is no one whom she fed or bore witness to earlier, let her bring the expiation [certificate] (patiyā) issued to her. --- 45

If the official document (kāgaja, i.e. the certificate) of expiation has been lost, there should be a purjī (an official short note) issued by the court ordering that she be granted expiation. Let her bring a true copy of it. --- 5

If the expiation was undertaken by official order, let her bring the official document of the pramāṅgī.6 --- 6

No fellow-caste member who has eaten rice [with her] has showed up until today, 16 years after the expiation took place. [Is it enough] to show a copy of the phāraka7 without showing the official document relating to the expiation? The matter is not recorded in the syāhā8 the way it is in the purjī, nor is it recorded in the āvarje9 the way it is in the syāhā. [Furthermore,] it is not recorded in the [account book containing] total expenditures (jmmā kharca) the way it is in āvarje, nor is it recorded in the phāraka they way it is in the [account book containing] total expenditures. Now, I cannot be satisfied only with a copy of what is written in the phāraka. --- 7

If, irrespective of whether a fellow caste member has eaten rice with her or not, you [still] give [me] an order to eat [rice with her] without having made an inquiry into the [above-mentioned] evidence, I will, assuming all fellow caste members are present there and are ready to eat rice with her, also be present. I have no complaint [in that case]. --- 8

[VS 1934 (1877/78 CE)].10 .

Commentary

There is a series of documents relating to the same issue, some seventy manuscripts in all filmed in the NGMPP K-series: K_0118_0032, K_0118_0039, K_0118_0040, K_0118_0041, K_0172_0057, K_0172_0058, K_0172_0063, K_0175_0032, K_0175_0034, K_0175_0039, K_0175_0042, K_0175_0044, K_0175_0047, K_0175_0049, K_0175_0052, K_0175_0057, K_0175_0060, K_0175_0066, K_0175_0068, K_0175_0069, K_0175_0071, K_0175_0072, K_0175_0073, K_0175_0076, K_0175_0077, K_0175_0079 and K_0175_0080 (to be edited separately). These documents deal with a family dispute between Rājakumārī Pãḍenī (the lawfully married wife of Pṛthī Bahādura) and the complainant (her brother-in-law’s son (bhatijo) Samasera Bahādura. On the basis of these documents, it is known that this dispute arose in VS 1918 (see K_0175_0033) after Pṛthī Bahādura committed adultery with the non-widowed wife (sadhavā) of a 4th-generation cousin and with a similarly distantly related female cousin (cāra pustākī didī ra bhāujyū). After committing adultery, he fled to the Terai (Madhyadeśa) with his entire family and household personnel (see K_0172_0058). Later, Rājakumārī returned from the Terai and initiated a court case to get her legal share of the inheritance. Samasera Bahādura and his family tried to avoid giving her any property, accusing her of being guilty of willingly accepting rice from her incestuous husband and having sexual intercourse with him. Rājakumārī Pãḍenī for her part insisted on her just claim, mentioning the expiation (patiyā) she had undertaken by order of authorities and offering further evidence (see K_0175_0033, K_0175_0034 and other above-mentioned documents).

The fact that in the first paragraph, Samasera Bahādura Pā̃ḍe made his complaint in accordance with relevant articles of the Ain proves that the Mulukī Ain was by then in legal force. Two issues addressed in this paragraph are dealt with in the Mulukī Ain of 1854: (1) adultery committed with an affinal or blood relation (in this case, with the non-widowed wife of a 4th-generation cousin and with a 4th-generation female cousin), (2) the impossibility of granting expiation to anybody who willingly has eaten together or had sexual intercourse with an incestuous person.

Adultery committed by a Cord-wearing Kṣatriya caste fellow is the subject of the 116th chapter of the Mulukī Ain (see MA-KM 1854/116), consisting of 21 paragraphs. Article 2 addresses adultery committed with blood relations (hāḍanātā) traceable back to within 7 generations. The punishment for this offence is prescribed as confiscation of the offender’s share of property (aṃśa-sarvasva), removal of the sacred thread, shaving of the head, forced consumption of liquor and pork, downgrading of caste and exile—towards the west if the guilty party is from the east and vice versa—across the river. Further, rice may not be received from the offender, nor expiation granted him. Water, however, can be received.

The second issue is addressed in the 89th chapter of the Mulukī Ain, on religious judges (dharmādhikārko) (see KM-MA 1854/89). Article 2 of this chapter, as argued by Samasera Bahādura in the first paragraph of his complaint, explicitly directs the dharmādhikārin not to grant expiation to those who have deliberately polluted themselves, only to those who have not (bhorako mātra patiyā dinu). Further, he should grant expiation to any offender if ordered to do so in a lālamohara. For granting expiation to an offender who is not entitled to such, the dharmādhikārin was to pay a fine of 500 rupees and be dismissed from his post (see Michaels 2005: 67-68 and 92).

Samasera Bahādura, in the 4th paragraph of the present document, refers to Article 2 of the Mulukī Ain (see MA-KM 1854/89) when challenging the wife of his middle uncle to show him the patiyā-purjī issued by a dharmādhikārin, since Article 3 of the same chapter identifies dharmādhikārins alone as entitled to issue such a document. Despite the fact that the Mulukī Ain does not directly order dharmādhikārins to issue a patiyā certificate upon successful completion of the expiation process, Michaels (2005: 39) writes, referring to Articles 3, 20, 29 of the 89th chapter (see footnote 20 on the same page), that the certificate was an integral part of rehabilitation: “Part of the rehabilitation was a certificate (purjī) by which the former caste status was affirmed or reconfirmed. The dharmaśāstras also prescribed that all certificates of rehabilitation be issued in a written from.” In any case, the present text illustrates that dharmādhikārins did indeed issue patiyā certificates. Michaels presents an example of such a certificate issued in VS 1890, prior to the Mulukī Ain (see Michaels: 2005: 40).

In the 5th paragraph, Samasera Bahādura refers to the 2nd, 3rd and 6th articles of the 89th chapter of the Mulukī Ain. Article 2 prescribes the following general procedure for receiving patiyā: the person seeking to undertake patiyā goes to a court, amāla or ṭhānā, where a pūrji is issued to a dharmādhikārin stating that the petitioner is eligible to undertake patiyā and that patiyā should be granted to him. The dharmādhikārin will then grant him patiyā and issue a patiyā-purjī. Thus Samasera Bahādura’s challenge—if the patiyā-purjī is lost, show him the purjī issued by the court in accordance with the Ain—stands on firm ground.

Samasera Bahādura’s 6th paragraph is in accordance with Article 4 of the 89th chapter (see MA-KM 1854/89). This article permits the dharmādhikārin to grant patiyā only if an offence has not been deliberately (bhor) committed. In cases of deliberate offences, dharmādhikārins should grant patiyā only if ordered to do so by mukhtīyāras or because the king has issued a dastakhata or lālamohara to that effect. If patiyā is granted without a lālamohara in cases of deliberate offences, dharmādhikārins were fined 500 rupees and dismissed from their post.

The copy of the phāraka referred to by Samasera Bahādura in the 7th paragraph is on NGMPP reel no. K_0175_0032. It is basically a copy of the receipt which mentions that Rājakumārī Pãḍenī, sister-in-law of Samasera Bahādura, paid 2 paisā as expiation fee (prāyaścitta). Since Samasera Bahādura is not satisfied with the copy of the phāraka, his sister-in-law presented another true copy of the phāraka along with a patiyā-purjī (probably issued by the dharmādhikārin). These two documents are preserved on NGMPP reel numbers K _0175_0033 and K_0175_0034 respectively. I have edited them separately.